Graphic, essential; text, supportive: the image and text relationship in a graphic novel

by Mae Rosukhon

At an EdsQ meeting, Dr Cath Appleton introduced participants to the world of the graphic novel, where images take primary place over text, and the visual storytelling format lends itself well to sharing personal tales.

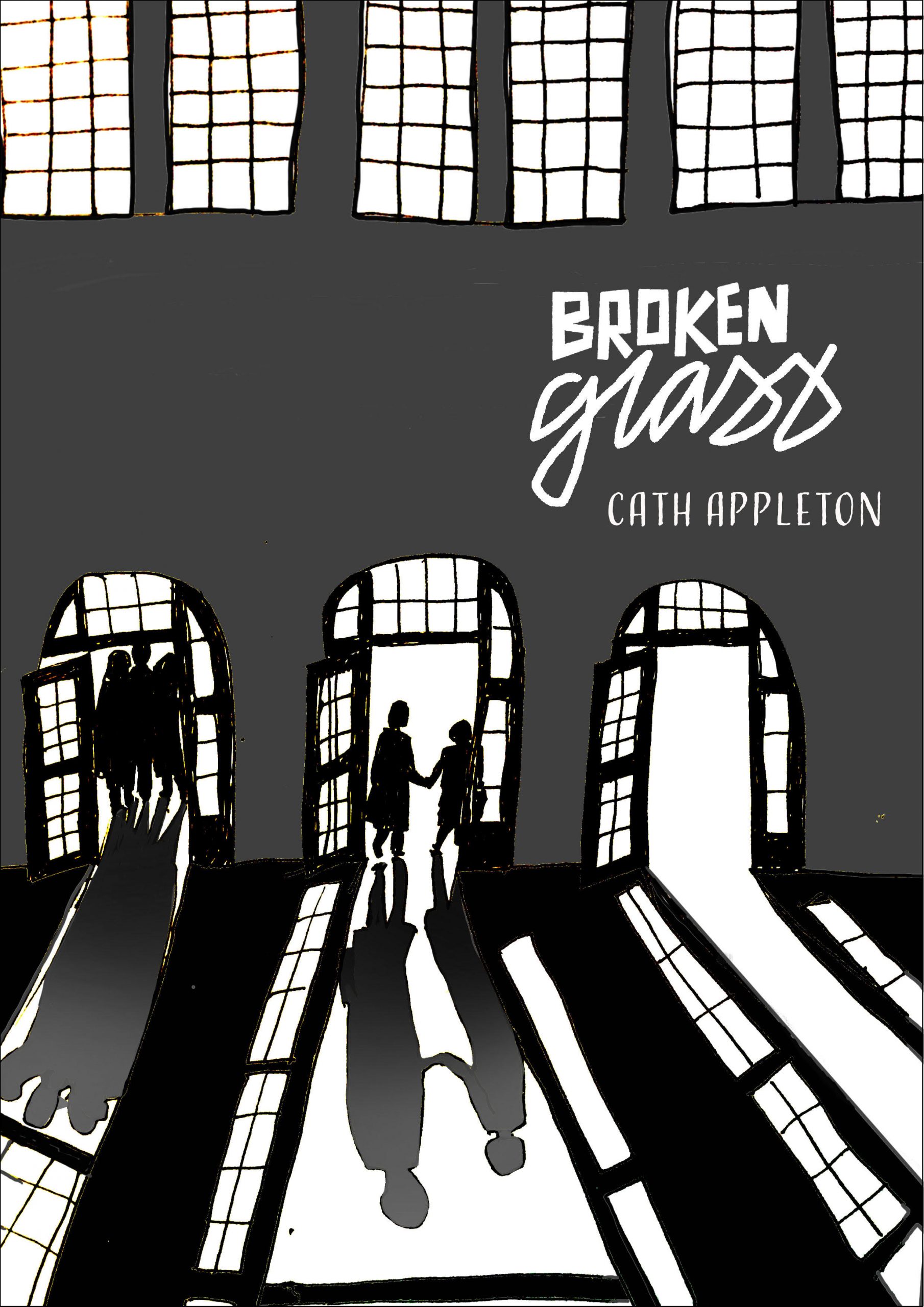

Her work Broken Glass animates the experiences of her mother Ella as a child during the Second World War and Cath’s own reflections on the intergenerational trauma that was an important, if invisible, presence in her relationship with her mother.

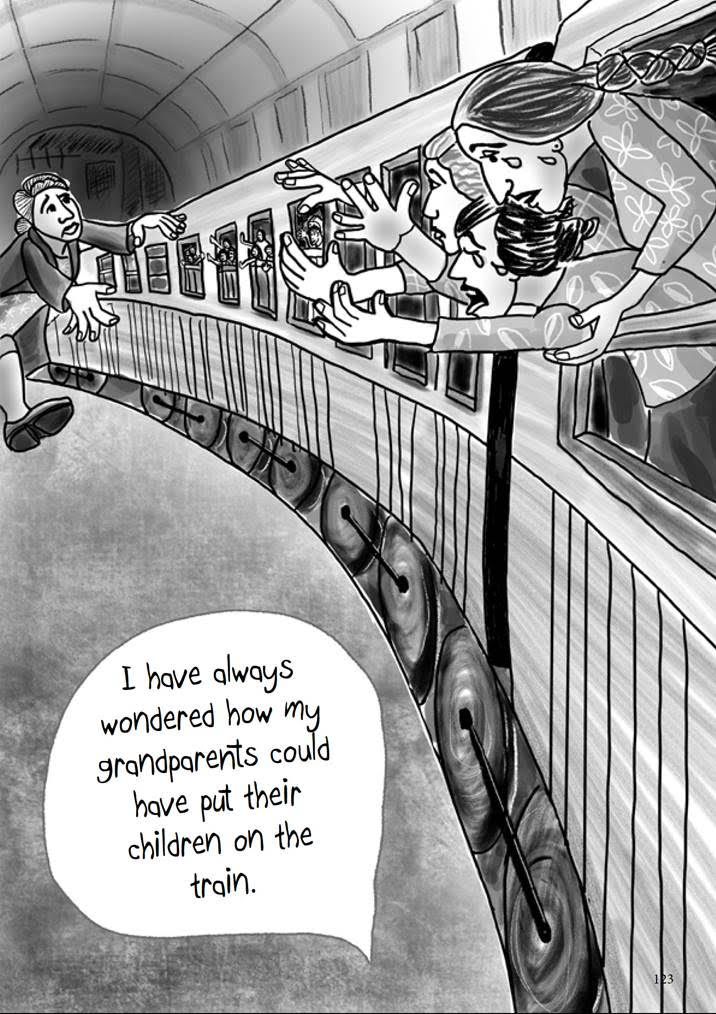

About 10,000 refugee children across Germany, Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia were sent to Britain before World War II officially started. Their families put them on the Kindertransport trains, a mission to take Jewish children to safety far away from the oppression of the Nazis. It brought them some physical safety, but what about emotional safety? Ella was only 10 years when, along with two older sisters, she was sent to England. Cath writes: ‘I have always wondered how my grandparents could have put their children on the train.’

As readers, we also accompany Ella on that train and onto her life journey. We see the children’s hands reaching out of the train, with tears running down their faces, and from that moment Ella’s parents turn into people she only knows on paper. Adjusting to a new life in England, Ella grows up, marries, has children of her own, and has stuffed away the memories of what happened in her youth. She escapes into travels and the arts, but the darkness and traumas visit her mind and settle in her body. As Ella’s daughter, Cath sees the demons are still present but doesn’t know how to help her mother deal with them.

And we follow her too, as she journeys into her family’s past. The ‘history was unfathomable’, she writes, of what happened in Europe at this period of time. And it was still present to her, as the reader sees her standing in the middle of her family’s pain. But it was also time for her to ‘clean out my inheritance’.

Personal experience

The graphic novel can successfully capture non-fiction, Cath said, as she blends personal experience into the context of the historic period. Where graphic novels differ from comics is that they tend to capture one longer story rather than being short and serialised. Graphic novels can also connect with readers in different ways to traditional text-based literature.

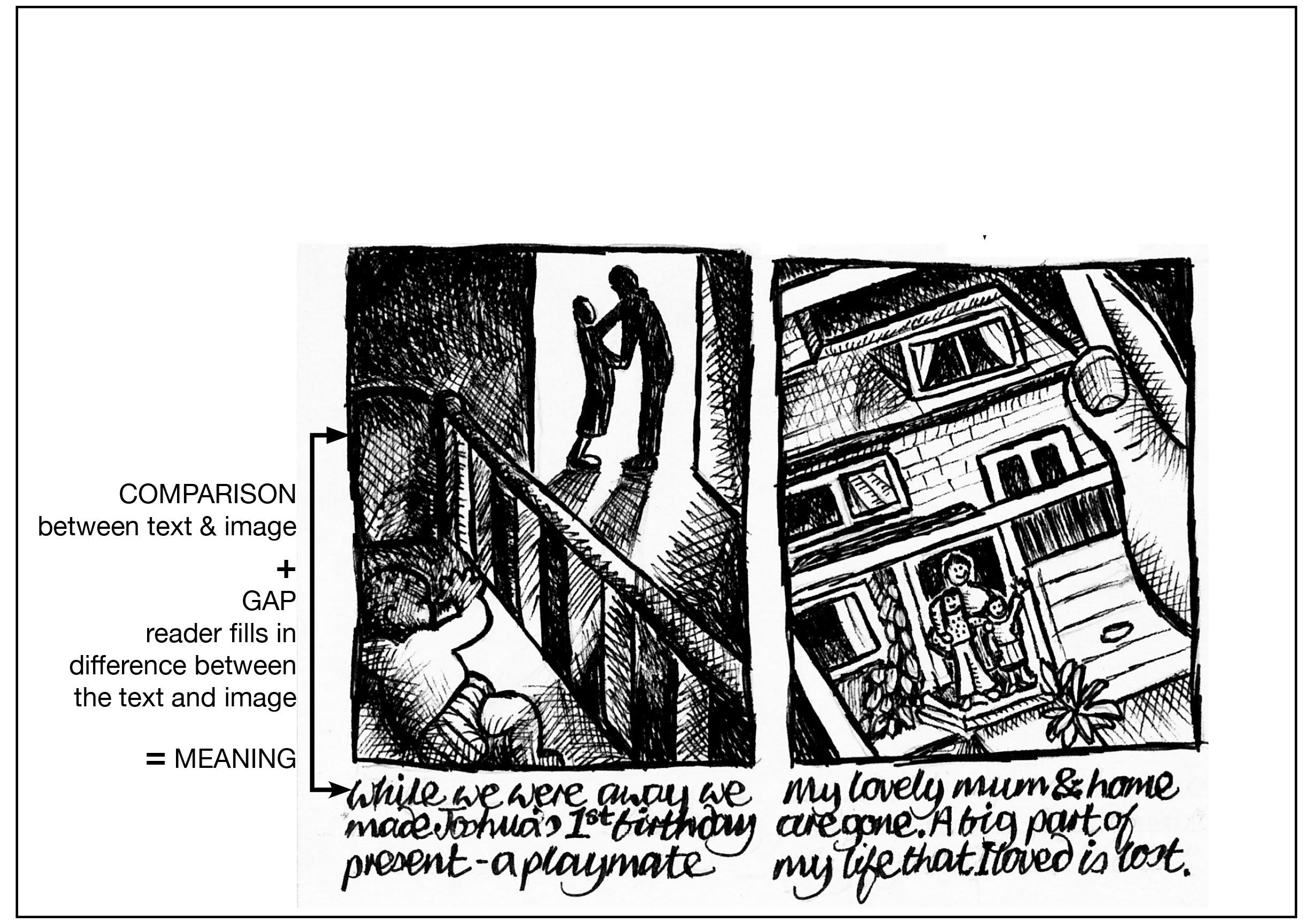

Moving from one panel to the next on the page is an easy way to follow the storytelling path. But reading is not always linear, and flexibility can be incorporated in image-making. From a blank page, inventiveness and creativity can flow. Cath’s process, in fact, was to keep minimising the words and let the images hold the story as much as possible. The gap between the panels is where meaning can be drawn, left to the reader’s imagination to build understanding. Sometimes the reader’s eyes go back and forth from image to image, making meaning in a process of comparison. Far beyond illustrating text, the images are the essential elements and can blend and incorporate text within it.

Emotional struggles

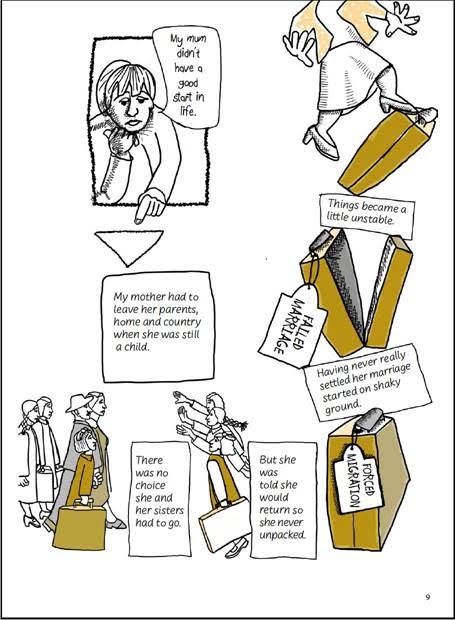

Graphic novels also allow for clear representations of visual motifs and metaphors. A suitcase is used throughout Broken Glass to connect to the emotional struggles of the two female protagonists. It literally is the emotional baggage that holds Ella’s anxieties, heavy with mental burdens, standing upright on shaky foundations. And it becomes a safe spot to hide herself away to find comfort in what is familiar. The suitcase remains when Ella leaves, and Cath is left to clear out her emotional inheritance, the intergenerational trauma.

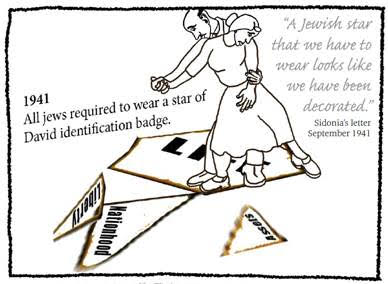

To depict the social foundations falling away from her grandparents’ lives in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, Cath draws her grandparents dancing on a thin Star of David. Sharp fragments break from the star as their society and liberties are taken away from them. The tightening grip between them breaks apart on a day in 1942 when they have no footing left, and they are sent to a labour camp and onto an extermination camp.

The author’s choices are all considered and conscious in writing a graphic novel. The storytelling technique engages readers to connect the images and words on the page, inviting them to consider what is there and what isn’t. As editors, graphic novels could be read in a way closer to picture books for those with experience editing these books. But graphic novels are really in a class of their own in the way readers are positioned to understand and interpret the text. Because of this, an editor should work very closely with the author throughout the editorial process. Broken Glass is a touching work of how family history, identity, trauma, past and present, and fact and fiction, can all be blended and presented into a healing form of literature.

Dr Cath Appleton is a visual storyteller, designer, academic and researcher. Broken Glass is her first graphic novel.

Note: Broken Glass is still in creative production at the time of writing and graphics presented in this piece are in draft form.

For more on graphic novels, see:

Gestalt Publishing, independent Australian graphic novel publishers

Magabala Books, independent Indigenous publishers

Graphic Medicine, exploring the intersection between healthcare, comics and communication

Some graphic novels noted by Dr Cath Appleton:

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

Stitches by David Small

Becoming Unbecoming by Una

The Arrival by Shaun Tan