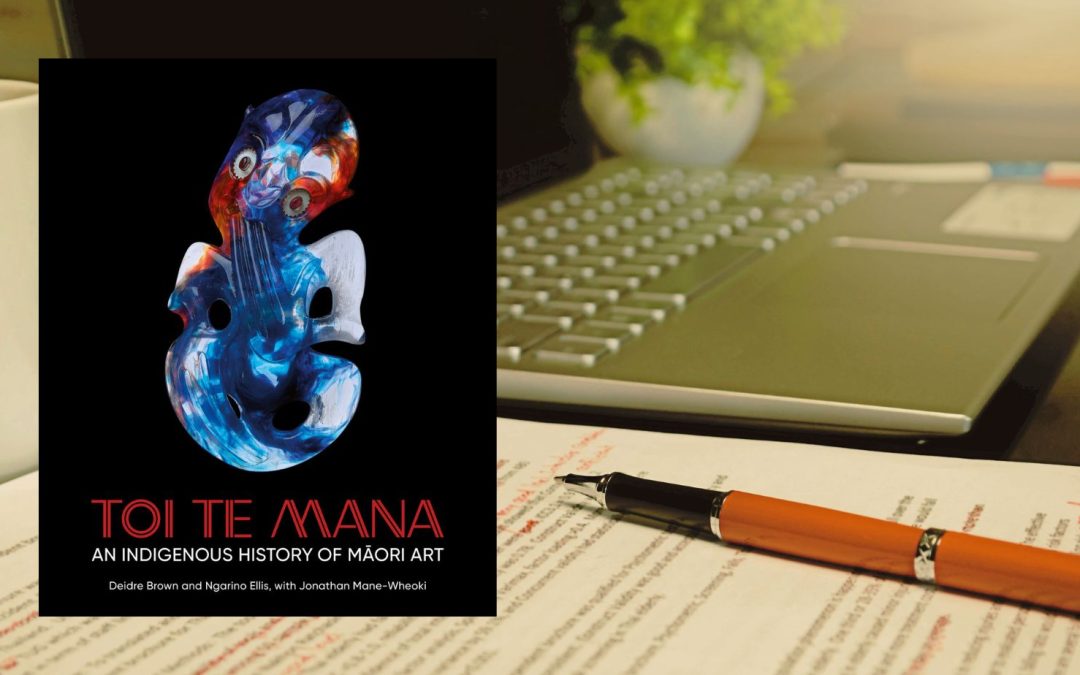

Earlier this year, Toi Te Mana: an Indigenous history of Māori art, published by IPEd organisational member Auckland University Press (AUP), was shortlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. More than a decade in the making, Toi Te Mana is a 616-page illustrated nonfiction book with several authors and hundreds of images requiring permission from the responsible whānau, marae, rūnanga or iwi authority. We spoke with AUP Publishing Associate Lauren Donald about editing this significant project.

Tell us about your role at AUP.

I’m a publishing associate within a team of five here at AUP. My time is split fairly evenly between marketing and editorial. In my marketing work, I organise book launches, support our publicists and manage digital marketing, among other things. On the editorial side, I project manage new titles and support the rest of our team with correction checking and proofing.

I currently have three titles under my wing, including an illustrated biography, a Māori translation of Macbeth, and a history of immigration in Aotearoa. I’ve also been dabbling in poetry acquisitions, so I have a few unread manuscripts sitting on my desk too.

Tell us about Toi Te Mana.

Toi Te Mana: an Indigenous history of Māori art, by Deidre Brown and Ngarino Ellis with Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, is a fully illustrated 616-page account of Māori art from early ancestral waka right through to contemporary artists featured at the recent Venice Biennale. Across 19 chapters, the authors explore a wide range of art practices, such as ngā toi whenua (rock art), ngā whare (architecture) and ngā kākahu (textiles). They also discuss toi Māori in the context of individual artists, movements and events, both here in Aotearoa and internationally.

It sounds like a substantial project! Can you share more about it?

The scale of this project was significant, and the book was around 12 years in the making. The authors began writing in 2012 after receiving a Marsden grant. The text was diligently copyedited in late 2020 by freelance editor Gillian Tewsley, and I joined this project in 2021 to help gather the 500+ image files and clear permissions.This image research took around three years and was a major learning curve for us in terms of identifying and seeking approval to reproduce images of these taonga.

In Aotearoa, iwi Māori exercise rangatiratanga over their taonga under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, so reproducing images of them requires permission from the responsible whānau, marae, rūnanga or iwi authority. From late 2023, once most of the images were compiled, we then shepherded the book through design, proofing and indexing with the help of our freelance project editor, Sarah Ell.

We celebrated the book launch at Waipapa Marae in November 2024, and we were excited to see Toi Te Mana being published internationally in February 2025 by the University of Chicago Press.

Are there things specific to illustrated nonfiction that an editor might need to be across?

The nuance of illustrated nonfiction titles is that they are – obviously – illustrated. Ensuring that the text is consistent with the visual elements of the book, and that the captions are accurate and navigable, is incredibly important.

Within large-scale books such as Toi Te Mana, the space between page 5 and page 500 reflects years of writing and research. The editing and proofing stages are essential to make sure the book is cohesive throughout.

What about the cultural considerations? What kinds of things did you need to be aware of and how did they shape the editorial process?

We took particular care to respect the authorial voice in the chapter written by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, who passed away in 2014. This meant consulting closely with Deidre Brown and Ngarino Ellis on any edits for this chapter.

Our work also respected the interweaving of te reo Māori within the text:

- We didn’t italicise kupu Māori as te reo Māori is not a foreign language.

- We made sure to use macrons correctly. Also we considered dialectical and historical spellings, particularly around the use of kupu and ingoa Māori.

- We recognised the complexity in providing English translations to kupu Māori ( translations are often over-simplified and lose nuance). We would typically only provide translations where essential for new concepts, though in Toi Te Mana we had to be aware of our international readership. This resulted in the inclusion of a kuputaka (glossary).

Were there any challenges editing Toi Te Mana?

The length and the breadth of the book. Fortunately, Toi Te Mana has a clear structure (3 parts, 19 chapters, 39 textboxes), which helped break down the monumental task. Making sure there was consistency in style and fact across the text, and across the different authorial voices, required both a keen eye and stamina.

The image captions (which ranged from short copyright information to longer, contextual paragraphs) were written almost three years after the text was copyedited, meaning these needed to be edited carefully. Often it was the body text that required updating as we learned new information during the image research. In many instances, kaitiaki would request to see the text written about the taonga in question, and some kaitiaki provided corrections or further context as a result.

Proofreading was integral due to the number of people who had been involved with the book, and the time that elapsed between edit and first pages. We worked with two freelance proofers on this, one for general proofing with an art-history focus and the other more specifically for Māori content.

Do you have any advice for an editor working on a large illustrated nonfiction project or an Indigenous project?

Don’t underestimate the value of time spent working together, kanohi ki te kanohi, on these large-scale, complex projects. The mahi is always easier when you have good relationships.

You have to accept what you don’t know and expect to make mistakes as a result. Learn from them. Talk to others about them. Recognise that you might not always be the most appropriate person to do the work (but you might have to do it anyway).

You must be flexible with timing. In 2012, no one would have predicted our publication in November 2024. All of ngā kaituhi, ngā ringatoi, ngā kaitiaki, ngā kanohi hōmirohiro me ngā kaimahi working on projects such as these are incredibly busy.