What do the books on your shelves say about you? Do you keep them all and never part with any? Are they a varied representation of different stages of your life and your interests?

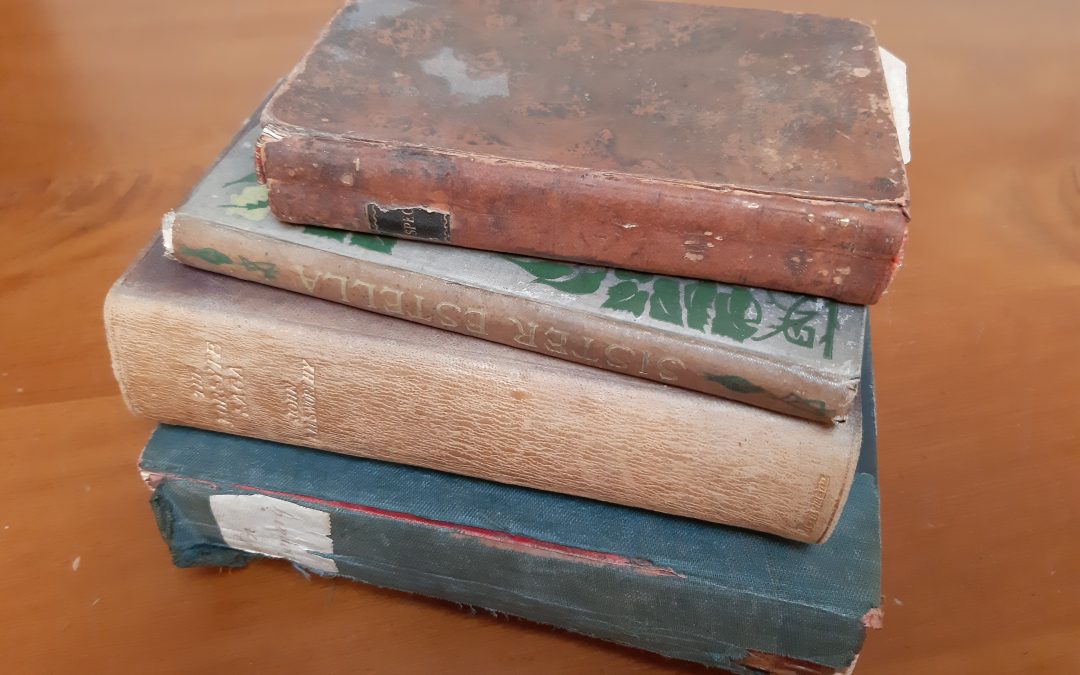

The other day I was gazing over our hall bookshelves, thinking about the books I had that had belonged to my grandparents. How had I come by these books and what did they tell me about my long-dead grandparents?

My paternal grandfather, Arthur, was by far the biggest donor to my library. I was just 12 when he died unexpectedly. My grandmother, Miriel, who was not quite well herself, encouraged me over the following years to help myself to his books. Arthur had been a teacher, and I recall my enthusiasm for his reference books, acquiring a dated but much loved library of English history books, 19th century poetry compilations and commentaries on Shakespeare’s plays. I also snaffled many of his Classics illustrated versions of classic stories which Arthur had used for his remedial reading classes in the 1970s. The most-used book I have of his is Cassell’s latin dictionary (1909) which I used at school in the fourth form. My name is listed under his on the first page. Looking at those books, I see the man whose enthusiasm for learning was lifelong.

Arthur plays a part in the story of the only book I have from my paternal grandmother: a 1927 edition of The Forsyte saga. In 1927, the two of them had been courting for a couple of years and Arthur presented Miriel with the volume for her 21st birthday. The inscription inside says “Happy birthday! Arthur” followed by the date. A year later they were engaged. Perhaps love wasn’t spoken of so much in those days. Grandma gave the book to me when I was 15 and she was in the process of moving out of her house into a rest home. In some ways, I wish she had given me one of the picture books we had read together when I was younger. But perhaps this had more meaning to her than I am aware of.

My maternal grandmother, Margaret, was born in Edinburgh long enough ago that she remembered the bells tolling for the “old queen’s” death. Her mother’s premature death had meant that, despite her teacher’s pleading, 12-year-old Margaret was removed from school to keep house for her father and brother. She came to New Zealand after World War I, and a journey like that would mean that most books would have been left in Scotland. The one book I have of hers was awarded to her by her school for “progress”. Four years after that award, Margaret’s mother was dead and her schooling was over. Another few years later, her father had died too. Margaret lived to 97, and although she never mentioned the book and I don’t know how I came by it, I do know that the death of her mother cut her childhood short. This book must have been a reminder of happier times.

Margaret’s husband, Percy, died before I was born. Everything I know about him is second-hand – like the books he used to love. His vast and eclectic library ended up in my parents’ house, and when the time came for my father to sell the house, many of these old books ended up in a skip. (Yes, we culled first!) Percy was born in 1893; he was a Victorian. Thanks to him my childhood was furnished with parlour games and humour from Foulsham’s fun book and old songs from his glee books. He had a taste for risque Edwardian humour too. I did save one of his books from the skip: The spectator, Vol IV (1793), printed at “No. 21, Paternoſter-Row”. I couldn’t be the one to throw away a book that had survived for well over 200 years. My father assured me it was worth nothing, but when I look at it, I see a man I never knew browsing a second-hand bookshop and delighting in his find. That is something I understand, and this is our connection.

So what do the books on my shelves say about me? They say that for me, books are not just about what is between the covers. They can span generations and form bonds between people who have never lived in the same time as each other. They say that my books are my friends – and my family.

By Caroline Simpson AE

EdANZ President